When I hear the term “arthritis” thrown around in relation to sporting dogs, I usually cringe. Often, it’s from well-intentioned folks saying things like, “He’s getting stoved up from arthritis in the back end,” or “We retired ol’ Red at 7 because of shoulder arthritis.”

When I ask how it was diagnosed, the answer is almost always something vague like, “Well, because he’s limping,” or “The vet gave me some arthritis meds.” At this point, I’m genuinely surprised when someone says it was based on an exam and x-rays.

Here’s a news flash: Not every dog gets arthritis. Moreover, not every limping, lame, or older dog with mobility issues has arthritis. Unfortunately, this is something that has been perpetuated by the veterinary profession over the years. In school, from a mobility standpoint, we were essentially taught that these dogs are bones and joints, and if they had issues, it was probably related to one of those two things. If not surgical, then an anti-inflammatory was likely the answer.

Throughout my career, I’ve taken over the clientele of a retiring vet four different times, two of those through clinic purchases. As part of those purchases, we offered a free exam for existing clients needing drug refills since we needed to establish a valid veterinary client-patient relationship to prescribe meds. I was blown away by how many people would get downright angry when I suggested not refilling the anti-inflammatory based on exam findings and their own reports that they didn’t know if it was working. They would accuse me of trying to pull a fast one on them, even though the exam was free, and I was suggesting they stop spending money each month on drugs that weren’t helping their dog. It took an entire conversation to convince them that I wasn’t making any money from the conversation and had no ulterior motives.

These people had been giving the drugs for so long that they assumed it was a necessary part of their dog’s life and weren’t willing to quit. This isn’t to say that I never have dogs on long-term meds, but I believe that the vast majority of dogs on them don’t need to be. The reason for this disconnect is that, for so long, we’ve assumed that if a dog was limping, it was a joint problem.

Let’s explore why this assumption is so wrong.

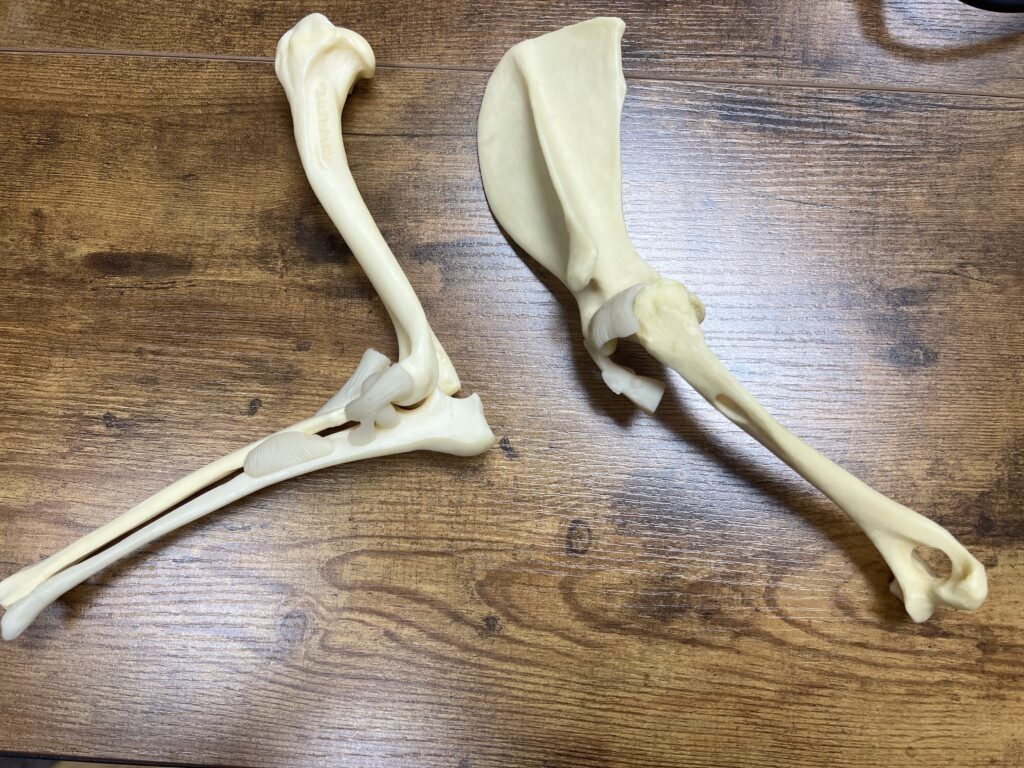

Take a look at the images below:

You’d likely recognize the first image as an animal pelvis, but without being certain of the type. In the next image:

Only a few of you would quickly identify these as the elbow and shoulder joints. Now, if we examine an image of a real-life dog:

You’d have no problem pointing out the rear end, elbows and shoulders.

The reason you are able to do this is that there are a lot of other tissues that make up a dog besides just bones and joints. In fact, in a dog, roughly only 12-13% of its body mass is bone, whereas 45-60% of it is muscle. Seems pretty foolish that we focus so much on such a relatively small percentage of the potential problem, right?

Now, I’m not writing this post to say that arthritis doesn’t exist or can’t be devastating—it does, and it can be. What I’m saying is that there is a lot of muscle, nerves, skin, and fascia that can also cause issues and discomfort, and for the most part, these have been ignored by the veterinary profession. In a well-bred hunting dog, out of lines that have been routinely health tested, outside of cruciate ligament tears, there are many issues that can occur that don’t involve the joints.

Here’s the other part that frustrates many people: When these other tissues are involved, the fix usually involves owner involvement, a cooperative dog, and time. If a bone breaks, it’s going to heal in 8 weeks, typically. If we do a TPLO to correct a cruciate ligament tear, most times, we can have that dog back in the field around 12 weeks. However, when soft tissues are involved, they don’t follow the same defined timeline, and this is very frustrating to most people.

I recently completed my first half-marathon after a 12-year layoff from running due to soft tissue issues that I thought were not fixable. Once I got into the right hands, they became manageable (note: I didn’t say cured), and I’m back to running. The crazy part is that for many of these issues, it wasn’t necessarily an inaccurate diagnosis—it was that the approach and treatment didn’t align with my goals. I was completely functional in most areas of my life, and so by most medical standards, I was fine. It wasn’t until I got into the hands of a performance-minded physical therapist that we started attacking the problem from the perspective of a return to performance.

Do I now need to spend an hour most nights using a lacrosse ball on my feet, a foam roller on my back, and doing maintenance exercises and stretches that I neglected in my 20s and 30s? Yes, but it is worth it to me to spend that time in the evenings to allow me to keep running.

With our dogs, there are options for keeping them in the field, but it requires a time investment from dedicated owners. It isn’t just a matter of popping a pill or using some new piece of equipment. I get that this isn’t in the cards for a lot of people for various reasons. I’m not here to judge the decisions anyone makes. My role is to determine the problems and offer options for a given problem. In too many cases, I don’t feel all of those options are discussed.

There are a few key items to understand to determine if you are going down the path of fixing a problem versus speculating about a problem or just throwing drugs at one. First and foremost is getting an accurate diagnosis. This is going to be a combination of your dog’s symptoms, your vet’s exam findings, and any confirmatory diagnostics like x-rays. Honestly, in very few cases can you have just two of these three and make an accurate diagnosis. I have had dogs come in with classic ACL symptoms—non-weight-bearing in a rear leg, pain, and even drawer movement in the joint—only to take an x-ray and find cancer. Until we complete the diagnostic process, we are just making a guess.

Once you have a diagnosis, it is important to understand your options for treatment. This may range from surgery to drugs to rehabilitation therapy and any combination or range of options in between. Where I would caution you is if you are offered extremes without discussion. For example, responses like, “There’s nothing we can do,” “You have to do this one surgery,” or “Here are some drugs.” Rarely is the answer that there is nothing we can do, though in some cases, like with certain cancers, this may be true. Likewise, with surgeries, there are often options and a discussion to be had. On the drug front, there will always be drug options, but we need to know why we are using them and what our goal is. You want to find a veterinarian who is a partner in addressing your dog’s issues and will help get your dog back to an active lifestyle.

The important thing to understand is what your goal is with these treatments. Are we masking symptoms, treating a problem, or managing it?

In the upcoming posts, we will take a closer look at the joints we most commonly see issues with our hunting dogs. We’ll dive into the hips, knees, elbows, shoulders, and back, exploring each in detail.