When it comes to canine joints, the hip is often the most talked about—largely due to the long-standing practice of hip certifications through the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA) – it’s been around since 1966. However, despite its common discussion, the hip joint is frequently misunderstood. In this post, we’ll break down the basics of hip health, common screening methods, and treatment options, especially for athletic dogs.

The Structure of the Hip Joint

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint, made up of the femoral head (the “ball”) and the hip bones (the “socket”). A ligament connects the head of the femur to the hip, and a substantial joint capsule holds everything together. In a healthy dog, this well-formed joint functions smoothly and typically remains free of arthritis unless other issues arise.

Screening for Hip Health

There are two primary methods of screening for hip dysplasia: OFA and PennHIP.

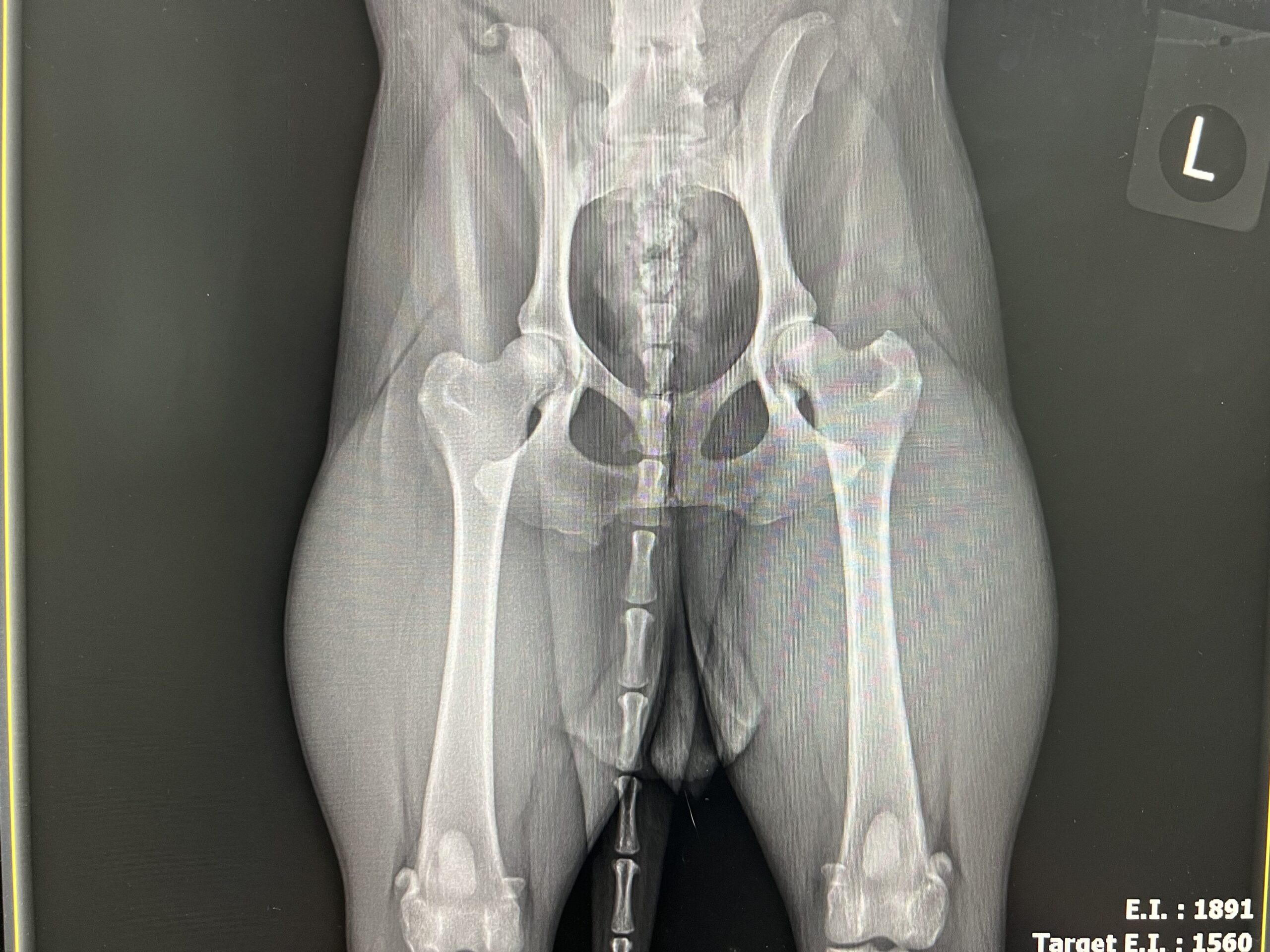

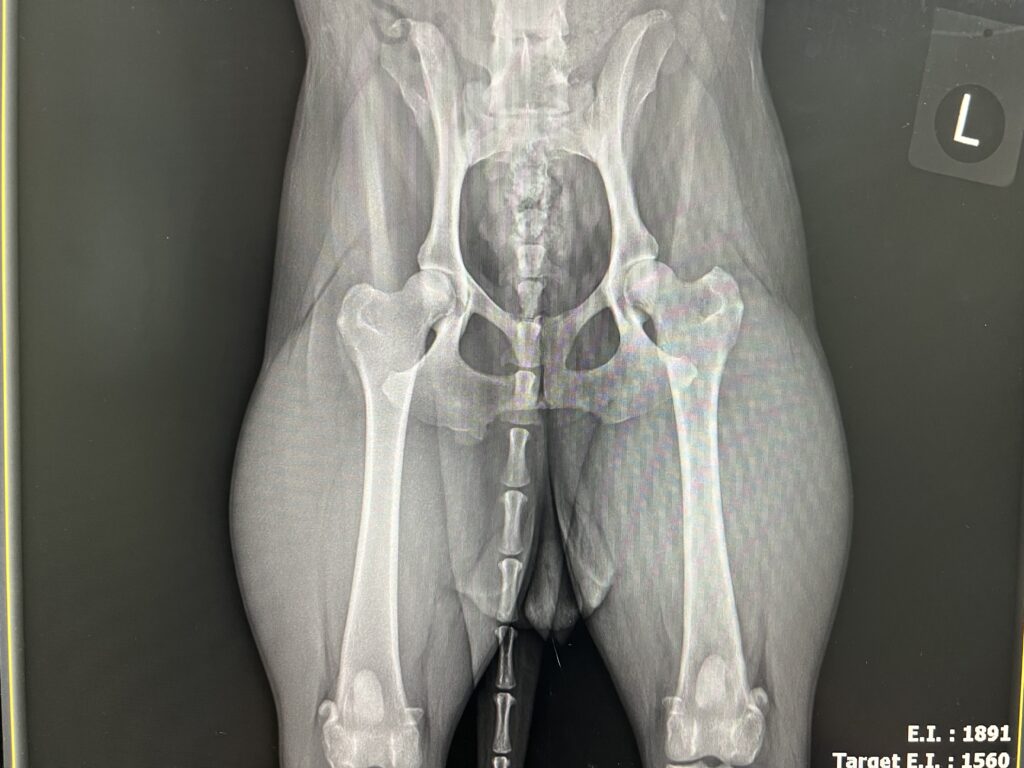

- OFA Certification — The OFA process involves a single X-ray taken with the dog on its back and legs extended. This image is then sent to three radiologists who generate a score based on their assessment. While OFA certification is helpful, it does have some subjective elements. There’s also an ongoing debate about whether the films should be taken while the dog is awake or sedated. In my experience, sedation doesn’t dramatically affect the results. While awake dogs may have tighter hips due to muscle tension, positioning can be manipulated under sedation. Ultimately, great hips will look great regardless, though positioning may influence borderline cases.

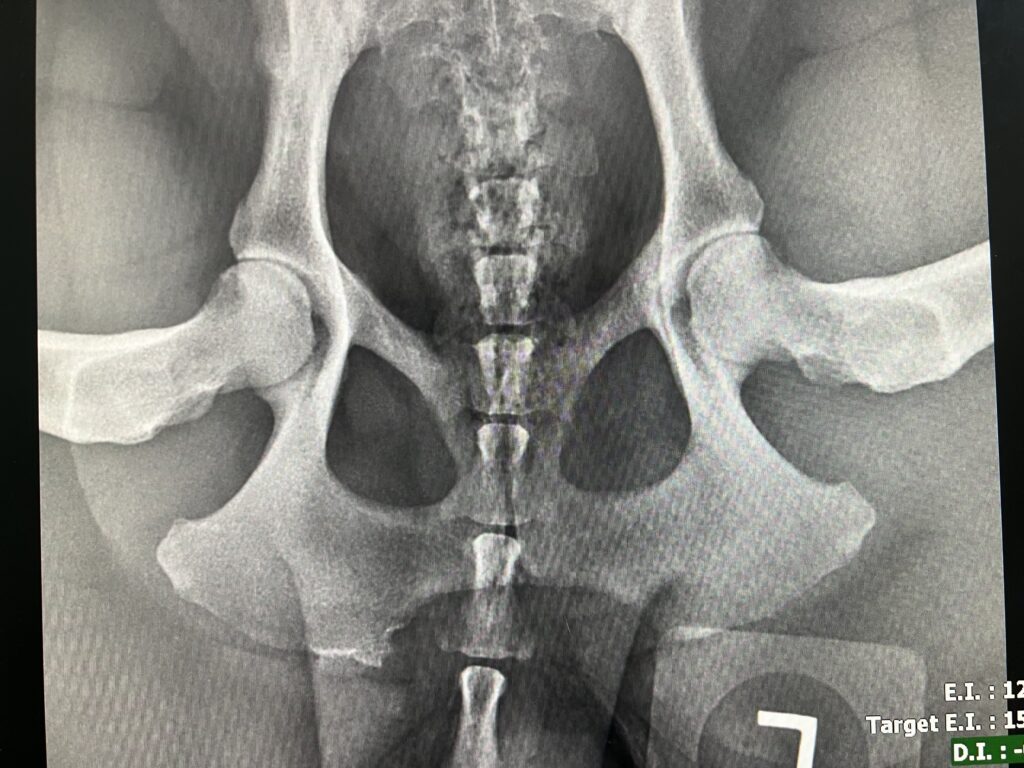

- PennHIP Certification — PennHIP, on the other hand, provides a more comprehensive evaluation. The dog is placed under anesthesia, and in addition to the standard extended view, a compressed and distracted view is taken to measure the distraction index (DI)—a measure of how far the hips can be displaced from the joint. The DI is compared to breed averages, making this method particularly useful for breeders. One major advantage of PennHIP is that it can be performed as early as four months of age, whereas OFA certification isn’t possible until 24 months.

In breeds with smaller populations, PennHIP numbers used to vary significantly, but now, with more data, assessments in common breeds have become more reliable. Some breeders worry that failed OFA dogs might skew PennHIP results, but I believe this is less of an issue in the vast majority of our hunting breeds. It certainly will be an issue in small obscure breeds, but I would contend that a small PennHIP population is only one of many potential problems in a small genetic pool…a topic for another day.

Recommendations for Breeders

For breeders, my typical recommendation is to pursue both OFA and PennHIP certifications. Many clients are more familiar with OFA, but PennHIP allows for earlier evaluations, enabling breeders to make informed decisions sooner. However, this doesn’t mean breeding dogs earlier—it simply allows for better planning, especially in cases where hip quality may be in question.

It’s important to remember that even dogs from generations of excellent hips can still develop hip dysplasia. Genetics, environment, nutrition, and development all play a role. As a breeder, it’s crucial to be transparent, offering health clearances while making it clear that you cannot guarantee against every possible issue. I’ve often said if I was breeding dogs I would NOT have a health guarantee. I would utilize all available health screening tools, make this information readily available to puppy buyers and then educate them that they are buying a living thing whose growth is influenced by so many factors other than genetics. They are either committed for the life of the dog or not. It is not a piece of equipment that can just be “exchanged” or “refunded.”

Hip Dysplasia: What It Means and How It Affects Dogs

Hip dysplasia occurs when the hip joint is not properly formed, leading to a shallow socket, a blunted femoral head, joint laxity or some combination of these factors. However, a diagnosis of hip dysplasia on an X-ray doesn’t always translate to clinical symptoms. I often see athletic dogs with terrible hips on X-ray that function just fine. In such cases, keeping the dog lean, active, and well-muscled is key to minimizing discomfort and maintaining function.

Early screening is critical, particularly for dogs with a family history of hip issues or for breeds prone to dysplasia. If caught early, a program can be put in place to help build rear end muscle and there are surgical options that can help prevent or mitigate the development of arthritis.

Surgical Interventions for Hip Dysplasia

- Juvenile Pubic Symphysiodesis (JPS) — If hip dysplasia is identified before the growth plates close, a JPS can be performed. This minimally invasive procedure alters the growth pattern of the pelvis to improve hip coverage. However, because few dogs are screened early enough, it’s rarely done. There’s some debate about whether dogs who have undergone this procedure should be marked in some way, as it can make future screenings misleading.

- Triple Pelvic Osteotomy (TPO) — Another option for young dogs is the TPO, which was popular when I was in veterinary school but is less common today. Like JPS, it needs to be performed before arthritic changes develop, making early screening essential.

- Surgical Options for Older Dogs For older dogs, two main surgical procedures are available:

- Total Hip Replacement: This is a complex surgery that requires expertise, and I’d recommend seeking out highly specialized surgeons for the best outcomes.

- Femoral Head Ostectomy (FHO): In this procedure, the ball of the ball-and-socket joint is removed. While it’s often successful, especially in smaller dogs, there is an art to ensuring the remaining tissues move freely. This is typically considered a salvage procedure, used when all other options have failed.

Key Takeaways for Managing Hip Dysplasia

Hip dysplasia can present as anything from an incidental X-ray finding to a debilitating condition. The most important points to keep in mind are:

- Screen your dog early to identify potential issues.

- Keep your dog lean, active, and well-muscled.

- Understand that there are multiple treatment options, not just one.

- If I had to choose one thing to manage hip dysplasia, it would be to keep the dog at a healthy weight. Don’t let your dog become overweight, as this exacerbates joint issues.

In the next part of this series, we’ll take a closer look at spinal issues in athletic dogs. Stay tuned!