As we continue our discussion about the canine knee, the focus with this post will be on the Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy (TPLO)—a surgical procedure designed to address cranial cruciate ligament disease in dogs. Unlike the extra-capsular technique that aims to mimic the function of the cruciate ligament, the TPLO eliminates the need for the ligament altogether by altering the biomechanics of the knee.

I want to start by being honest—I hated this procedure for the first half of my career. It took years of observation and experience before I changed my stance, and I want to walk you through that journey before diving into the details of the procedure itself.

My Initial Skepticism Toward TPLO

When I was in veterinary school in the late 1990s, TPLO was still under patent by its developer, Dr. Slocum. Because of this, only a select group of veterinarians—primarily boarded surgeons—were trained in the procedure. In today’s world people would likely take such an approach to maximize profit, for Slocum it was about protecting quality. This exclusivity made it difficult to evaluate the TPLO broadly and how it would perform once out of purely skilled hands.

Dr. Slocum passed away in 2001, and the patent expired around the same time, opening the procedure to a wider audience of general practitioners. This led to a flood of veterinarians learning and performing TPLO, many of whom only did a handful per year. As a result, I wasn’t seeing better outcomes compared to the extracapsular technique, a far less invasive method we discussed in a previous blog.

Why cut a bone in half when you’re not getting better results? That was my thought process at the time. More invasive procedures should offer clear advantages, and from what I saw in my early career, they didn’t.

What Changed My Mind About TPLO?

About 15 years ago, I started working with a surgeon who had performed thousands of TPLO procedures—by the time he retired last year, he had likely done 8,000 to 10,000 and he is only in his early 50s. I noticed a significant difference in the outcomes of dogs treated by someone with that level of experience.

The pivotal moment came when a hunting buddy’s English Pointer ruptured both cruciate ligaments. We opted for TPLO in one leg to speed up the recovery process, so we could do the second surgery sooner. The dog recovered so well that my friend insisted we use the TPLO on the second leg as well. That dog hunted that fall without missing a beat and went on to have a long, successful career.

From that point on, I started recommending TPLO for active, athletic dogs over 50 pounds. Over time, my recommendations have expanded to include dogs as small as 35 pounds (surgeons are comfortable going even smaller), and even older dogs (12+ years old) if they are otherwise good surgical candidates.

How TPLO Works

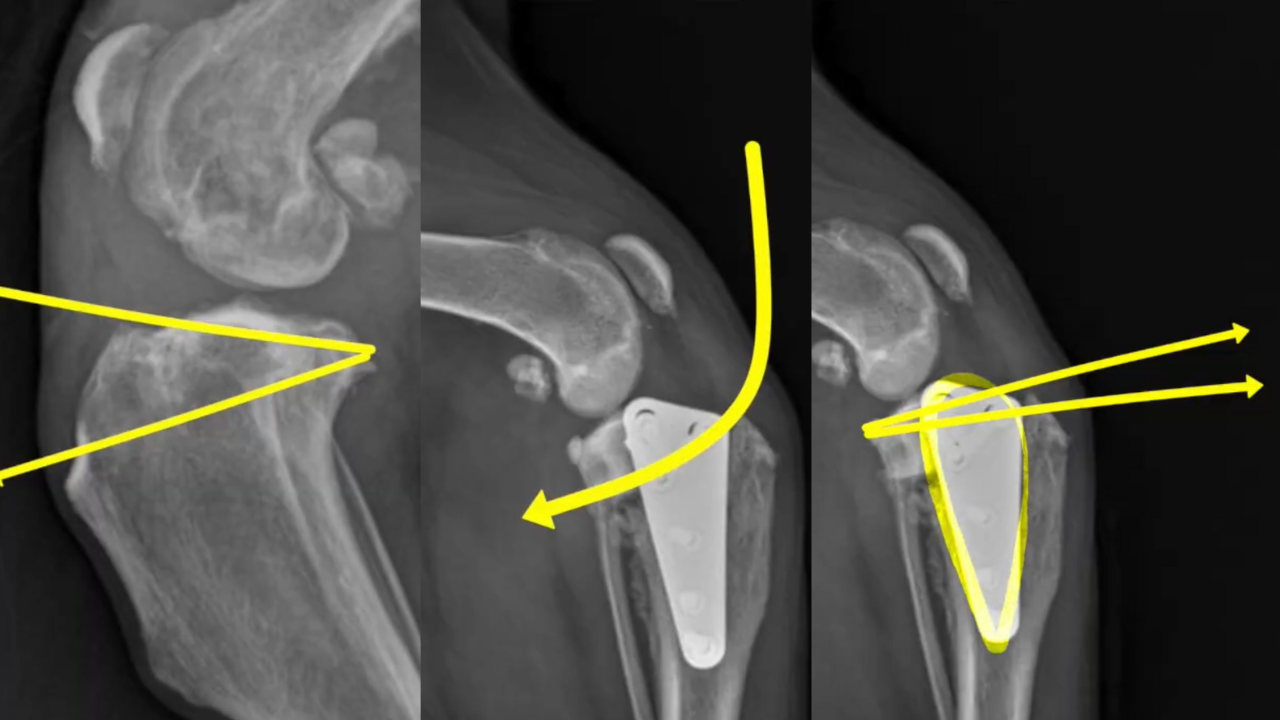

Unlike other techniques that attempt to replace or replicate the function of the cruciate ligament, TPLO changes the biomechanics of the knee itself. Here’s how it works:

- Joint Inspection & Meniscus Evaluation – The surgeon enters the joint, removes any torn ligament, and inspects the meniscus. If it’s damaged, the affected portion is removed.

- Bone Realignment – The tibial plateau (top portion of the tibia) is cut in a circular fashion and rotated to change the angle from its natural slope (20-24 degrees) down to around 5 degrees.

- Stabilization with a Plate – The rotated bone is secured with a metal plate, which holds everything in place while it heals.

By changing the angle, the TPLO eliminates the forward sliding motion (cranial tibial thrust) that occurs when the cruciate ligament is torn, meaning the knee no longer requires the ligament for stability.

The Debate Over Meniscal Release

One area of controversy in TPLO surgery is whether to perform a meniscal release when the meniscus is still intact.

- Dr. Slocum’s Original Theory – The meniscus should be released to reduce the risk of future tears, since TPLO does not replace the cruciate ligament’s function.

- The Opposing View – Leaving the meniscus intact helps preserve joint function and may reduce long-term arthritis risk.

Personally, I favor meniscal release based on my experience. I have yet to see post-op meniscal issues in dogs whose surgeons perform the release where I have had the opposite where a dog that did not have a release needed to have subsequent surgery. However, studies suggest no significant statistical difference in post-op outcomes between released and intact menisci. Ultimately, this is a discussion to have with your surgeon.

TPLO Success Rates & Risks

The good news is that TPLO has an overall success rate of over 90%, even when accounting for variability in surgeon experience. In the right hands, that number is likely even higher.

However, no surgery is without risks. Here are the major complications:

1. Plate Failure (1-4%)

Since the tibia is cut in half, strict activity restriction is crucial during the 8-week healing period. If a dog is too active, the plate can bend or break, leading to catastrophic failure.

Example: One of the scariest cases I had was a boxer whose owners called, distraught that the surgery had failed. Turns out the story they left out was that the dog had broken out of its kennel, sprinted up the stairs, crashed through a door, ran down the deck stairs and fence-fought a neighbor’s dog—all within a week of surgery! Miraculously, X-rays showed the plate was still intact.

2. Infection (Up to 14%)

Because the surgery introduces foreign material, infection is always a risk. Proper surgical technique, strict sterility, and careful post-op management help reduce this risk significantly.

3. Implant Issues (≈3%)

Some dogs develop reactions to the metal plate, which may require removal after the bone has healed. There is also ongoing debate over whether TPLO plates could increase the risk of bone cancer, though the evidence remains inconclusive and appears to be related to one specific plate type.

How to Ensure a Successful TPLO Surgery

The single most important factor in a successful TPLO outcome is choosing the right surgeon.

- Experience matters. A surgeon who has performed thousands of these will have superior outcomes compared to someone doing only a few per month.

- Not all non-board-certified surgeons are bad. Many non-boarded veterinarians perform excellent TPLO surgeries. The key is finding someone with a proven track record.

- Ask questions! Inquire about their complication rates, their approach to the meniscus, and their success with returning athletic dogs to full activity.

For many working and sporting dogs, TPLO is the best option for returning them to peak performance. While I once questioned its necessity, years of experience have made me a strong believer in the procedure—as long as it’s done by the right hands.

Final Thought: If your dog needs TPLO surgery, take the time to find an experienced surgeon and follow post-op instructions carefully. Doing so will maximize the odds of getting your dog back to doing what they love.